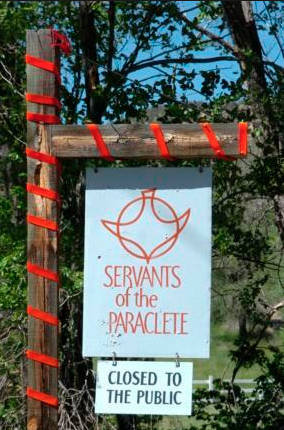

1. The Servants of the Paraclete complex in Jemez Springs, N.M. U.S.A;- 2. St. Luke's Institute, a Catholic psychiatric hospital in Maryland. U.S.A.;- 3. The Granada Institute, Dublin. Ireland

http://www.awrsipe.com/Doyle/2011/2011-01-11--paraclete_report.htm

Paraclete Report

January 11, 2011

Overview

The Servants of the Paraclete is the name of a Roman Catholic religious community of men. The community was founded in 1947 by Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald under the original patronage of Archbishop Edwin Byrne, Archbishop of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The name of the community includes the word "Paraclete" which is derived from a Greek word meaning "advocate" or "helper." This word is also used to describe the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit.

The community was founded for the sole purpose of providing assistance to priests with substance abuse or psycho-sexual problems. The original foundations were in New Mexico. In time the community opened houses in several other States and in foreign countries including the U.K. The Paraclete community provided treatment to priests who had sexually abused minors from its inception in 1947. In the 1990's it was faced with a series of lawsuits, all related to priests who had been treated by the community for sexual abuse of minors. By the end of the decade the Paracletes had ended their ministry to priests who had committed sexual abuse of minors, at least in the U.S. The Paraclete facility in the U.K., Our Lady of Victory Treatment Centre at Stroud, continued to treat sexually abusive priests until it closed in 2004.

Since the mid 1980's there has been controversy over the treatment methods used by the community and over the suitability and stability of certain of the Paraclete members themselves. The controversy began when it was revealed that certain guest-priests who had been serving on a temporary basis in local parishes had sexually abused minors while in treatment or had abused minors after completing treatment. This led to criticism of the treatment methods, supervision, and quality and effectiveness of after-care programs.

1. Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald and the Foundation of the Servants of the Paraclete

Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald was born in Boston in 1894. He was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Boston in 1921. He served in Boston area parishes until 1933 when he received permission to join the Congregation of the Holy Cross, a world-wide religious community. He was made rector of a college-level seminary for the community, and while in that assignment he developed the idea of founding a religious community of men who would serve troubled priests.

The Servants of the Paraclete, as the order is formally known, was originally an official religious community under the sponsorship and authority of the Archbishop of Santa Fe, New Mexico in the U.S. Although it had existed since 1947 it achieved its first level of official status in 1952. As the community expanded and as its mission became known not only in the U.S. but in Europe as well, the superiors petitioned the Holy See to be granted Pontifical Right status. This means that the community would be placed under the authority of the Pope. The decree granting this status was issued on Jan. 16, 1971.

Fr. Gerald circulated a request for support among Catholic bishops and received a favourable response from Archbishop Edwin Byrne of Santa Fe. With financial help from Cardinal Spellman of New York ($25,000), Fr. Gerald purchased 2000 acres near Jemez Springs, NM and set up his first foundation in a former Franciscan monastery. In the early decades the Paraclete facilities were not identified as treatment facilities but as retreat houses (cf. Affidavit of Fr. Joseph McNamara, Nov. 17, 1993, par. 5). Fr. Gerald was an intensely spiritual man with a high regard for the priesthood as an exalted and mystical calling. He firmly believed that the best treatment for the problems of the priests who sought his help or were sent to him by their bishops was a concentrated spiritual program. To achieve this end the guest-priests, as they were called, were obliged to participate in various spiritual exercises such as Mass, spiritual reading, meditation, common prayer, private prayer and periods of silent prayer and reflection before the Blessed Sacrament. The spiritual program consisted mostly of formal exercises arranged throughout the day in such a way that the guests had no time periods of more than four hours for any other type of activity.

Expansion. Fr. Gerald wrote to numerous U.S. bishops describing his goal of creating a retreat centre specifically for the renewal of priests with sexual and alcohol problems. Since there was no such resource in the U.S. at the time of the Paraclete foundation, the bishops generally responded favourably. Fr. Gerald was providing a resource that answered an obvious need. In 1950 Fr. Gerald wrote to Bishop Buddy of San Diego and told him that for the first time in the community's three year history the main monastery, known as Via Coeli (Way to Heaven) was filled to capacity and had to turn a priest away. He went on to state that at that time there were priests from 35 U.S. dioceses and 9 religious communities at Via Coeli.

There have been five general superiors of the order, known as Servants General: Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald, 1947-1969; Fr. Joseph McNamara, 1969-1981; Fr. Michael Foley, 1981-1987; Fr. Liam Hoare, 1987-1999; and Fr. Peter Lechner, 1999 to the present.

When the Servants received their first official status as a diocesan community in 1952 there were 17 members. The peak year for membership was 1968 with 112 members. The first period of decline was between 1971 and 1991 when membership decreased from 80 to 42 during that twenty year period. The second period began in 1992 when membership declined from 33 to 22 in 2002 (All statistics taken from the Official Catholic Directory between 1953 and 2002). If the Paraclete website reflects the current numbers, the community now comprises 15 priests.

The Paraclete mission rapidly expanded from the time of its foundation. The first facility and Paraclete community was in Jemez Springs, NM. In time Fr. Gerald opened a house in Albuquerque, the "Albuquerque Villa." The expansion went beyond U.S. borders:

1947: Jemez Springs, NM

1956: Santa Fe, NM; Neves, MN; Gallup NM; San Diego, CA

1958: Burlington, VT; Youngstown, OH

1961: British Virgin Islands; Stroud, England

1962: Rome, Italy; Santa Cruz, Mexico; Rapid City, IA; Chicago, IL

1965: Two houses in South America, one in Africa

1966: Dumfriesshire, Scotland

1967: Jallais, France

1971: San Bernardino, CA; St. Louis, MO

Decline. The Paracletes faced lawsuits and media scrutiny in the mid 1990's based initially on extensive sexual abuse by priests who had been guests at the Paracletes, notably Fr. James Porter, Fr. Jay Sigler and Fr. David Holley. The community terminated its treatment programs for priests with psycho-sexual disorders and began to close many of their houses. At the present time, the Paracletes list houses in Dittmer, MO., Albuquerque, NM and Tagayta City, Philippines. The order closed its house, Our Lady of Victory, in Stroud, England around 2004. There is a current listing for Our Lady of Victory Trust in Stroud, but it is uncertain if this is a Paraclete facility.

2. Professional Qualifications of Paraclete Members

The early members of the Paraclete community included men already ordained and assigned to other dioceses or religious communities. Like Fr. Gerald, they sought permission to transfer to the new community in great part because of the unique nature of the work. None of the early members, including Fr. Gerald himself, had professional credentials or training of any kind that would have aided in helping priests with alcohol or psychological problems. If a guest needed or wanted psychological or psychiatric help, he was referred to resources in the surrounding area.

Fr. Gerald wrote a report dated Sept. 30, 1966, in which he summed up the training program for members of the Paraclete community: "There IS a training program for Paracletes. It is a very fine and wide-spread kind of program: on-the-job training." He went on to state that the candidates for membership who were not yet ordained were trained in a program that "conforms to the standards which Mother Church has set up for the training of prospective priests." In 1967 following an internal dispute fueled by a highly critical report of Fr. John Murphy, the first two Paracletes were sent for professional training in psychology specialising in sexual deviation (cf. Richard Sipe Report, May 3, 2006)

A number of guest-priests who had received treatment at one of the Paraclete facilities in time became members of the community. There is no documentary evidence that any of these priests ever received specialised training in psychology or a related area, although it is entirely possible that some did receive such training. Among the guest priests who in time became either members of the Paraclete community or who became staff members at a Paraclete facility, there were several who had been confirmed as sexual abusers of minors.

Among the confirmed sexual abusers who have worked at the Paraclete therapeutic facilities have been:

a. Francis Luddy, Diocese of Allentown. Luddy admitted to abusing at least 5 minor boys. A civil trial in 1994 ended with an award of $1.5 million to two victims. Luddy went to the Paraclete facility in New Mexico for treatment and moved on to a position as administrative assistant and director of admissions.

b. Lane Fontenot, Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. Fontenot was convicted in 1986 and sentenced to a year in jail and two years treatment with the Paracletes. At least as late as 1994 he was still with the Paracletes and employed in an administrative position. (I have personal knowledge of his situation in 1994 insofar as his counselor, the late Fr. Michael Mack, was an acquaintance who had called me for canonical advice for Fontenot.)

c. John Feit, formerly a priest of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, then a member of the Paracletes. Feit pleaded no contest to aggravated assault in the attempted rape of a young woman in Edinburgh, Texas. Shortly after this assault he became a prime suspect in the murder of another young woman. In the 1960's he went to the Paracletes and subsequently became not only a member but a superior of one of their facilities.

d. Gordon MacRae, Diocese of Manchester, NH. MacRae pleaded guilty in 1988 to a sexual abuse charge and was sent to a Paraclete facility, Foundation House, in New Mexico. In 1990 he took a position there as assistant director. In 1994 he was convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to prison for 33 to 67 years.

John Feit had the opportunity to have the most significant impact on guest priests because of his leadership position. In 1972 he left the Paraclete community and subsequently married. He wrote reports in response to the charges made by Fr. John Murphy (see below) but most important, he was instrumental in returning Fr. James Porter to active ministry. Porter was credibly accused of sexually abusing many minor boys while serving as a priest in the Fall River Diocese. He was sent to the Paraclete facility in 1967, and while he was there John Feit was directly instrumental in allowing Porter to have weekend ministry assignments in New Mexico, where he abused more minors. Feit helped him find assignments in New Mexico, Texas and finally in Minnesota.

3. Internal Dispute over Treatment Modalities

Archbishop Edwin Byrne of Santa Fe was a staunch supporter of Fr. Gerald and was often referred to by Fr. Gerald as the "co-founder" of the Paracletes. As long as Byrne was Archbishop, Fr. Gerald had un-challenged control over the programs implemented by the Paracletes, which programs were completely spiritual in nature. Archbishop Byrne died on July 26, 1963 and was succeeded by Archbishop James Peter Davis, who had been the Archbishop of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Davis was appointed on Jan. 3, 1964 and resigned in 1974. In 1960 Fr. Gerald purchased a facility on an island in the Caribbean. He had originally been offered the island of Tortola by Archbishop Davis, then of San Juan. This venture did not work out and the Paraclete fathers then moved to the island of Carriacou. (The island episode will be covered below.) In 1965 Archbishop Davis ordered Fr. Gerald to sell the island (cf. letter of Archbishop Davis, 8-23-1965). An internal dispute coincided with the issue of the island. The dispute was over Fr. Gerald's control of the workings of the Paraclete ministries, his problems with administration and his reluctance and refusal to admit any type of psychological or psychiatric therapy programs. He distrusted any therapy programs and also distrusted Alcoholics Anonymous, refusing to allow such programs to be utilised as long as he had full charge.

Fr. Gerald's Approach is Challenged. Archbishop Davis began asserting more oversight and control over Fr. Gerald not long after he came to power in Santa Fe. During this period some of the Paraclete priests, notably Fr. William Tobin, superior of the community in Scotland, wanted to discuss other types of programs for the guest-priests, especially Alcoholics Anonymous. Fr. Gerald admitted that AA had helped many but he opposed it because it because it accepted the disease concept of alcoholism, a concept that was relatively new in the early 1960's even though it had been officially declared an illness by the American Medical Association in 1956. He believed that alcoholism was a moral weakness and could be "cured" by spiritual means (cf. letter of Fr. Gerald to Fr. William Kenneally, July 21, 1960).

Although Fr. Gerald would not interfere if a guest wanted to see a psychologist or psychiatrist, he would not require or even encourage this. His philosophy in this regard was supported by other members of the community, including Fr. John Feit. Both Frs. Gerald and Feit referred to the guests' problems as "weaknesses." Fr. Gerald said in a 1966 report that "psychiatric examinations for Paracletes have not been deemed necessary." Concerning therapy programs he said in the same report: "Insistence on mandatory therapy goes against the freedom and dignity of the human person as well as against acknowledged psycho-therapeutic techniques." (Report, Sept. 30, 1966).

The Vatican appointed Fr. David Temple, a Franciscan priest, to act as a "religious assistant" to the Paracletes to assist them in resolving their internal disputes. According to Fr. Joseph McNamara, Fr. Temple was to "serve as a brake on Father Gerald attempting to regain power in the United States." (cf. Affidavit, par. 28)

Fr. Bill Tobin, mentioned above, intended to bring up the matter of AA at the 1964 General Chapter, the general legislative meeting of the entire Paraclete order that took place every six years. Fr. Gerald heard of this and obtained permission from the Holy See to hold the Chapter by mail, which is how it was conducted. AA was not brought up and Fr. Gerald was re-elected as superior general of the order.

AA – The first professional program. Most of the guest-priests treated by the Paraclete community in the early years (prior to 1965) were there because of alcoholism or alcohol abuse. Fr. Gerald, in a letter to Bishop Durick of Nashville dated Sept. 10, 1964, said that one half of the priests treated were there for alcoholism. Archbishop Davis appointed Fr. Joseph McNamara superior of Via Coeli in August 1965 with instructions to implement lay therapy programs for the guest-priests (cf. Affidavit of Fr. McNamara, 11-17-1993, par. 20). Fr. McNamara set about implementing these instructions beginning with a program for treatment of alcoholics. He became convinced of the effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous and sent a request to Archbishop Davis that he be able to bring AA to Via Coeli and also hire a professional to run an alcohol rehab program that would supplement the AA program. Archbishop Davis agreed to both proposals. Fr. Gerald then tried to have the Archbishop remove Fr. McNamara as superior of Via Coeli, but this was refused by the Archbishop.

Fr. Gerald took the issue to the Congregation for Religious at the Vatican. The Congregation backed Archbishop Davis and supported his plan to involve AA as well as other lay therapy programs (cf. Ibid. par. 26).

The Participation of Psychologists. Fr. Joseph McNamara was appointed superior at Via Coeli in 1965. He hired Dr. John Salazar in 1966 as the first resident psychologist for the Paraclete programs. Dr. Salazar had first seen a Paraclete guest for evaluation in 1963 (cf. Deposition of Dr. John Salazar). Fr. McNamara also initiated other therapy programs in keeping with the orders of Archbishop Davis. The shift from a program based exclusively on traditional Catholic spiritual practices to a program described by Fr. Liam Hoare as a "holistic approach to our mission of spiritual rehabilitation" began in 1967 (cf. Affidavit of Liam Hoare, 3-23-1992, par. 22-23). This approach included spiritual, psychiatric and psychological counselling. The Paracletes contracted with psychologists and psychiatrists to provide the needed care and to assist in assessments and creation of treatment and after-care programs.

Dr. John Salazar was the first psychologist to work at the Jemez Springs facility on a permanent basis. Dr. Jay Feierman, M.D. was a consultant to the program between 1976 and 1995. Other psychologists who have worked at the facility have included Dr. Robert Goodkind, Dr. Sarah Brennan and two Paraclete priests, Fr. Michael Foley and Fr. William Perri.

4. Early Complaints – Fr. John Murphy's Report

The Holy See appointed Fr. David Temple as "Religious assistant" to the Paracletes in 1965. Fr. John Murphy, a priest from the Diocese of Lincoln, NE who had joined the Paracletes, sent a report critical of the conditions at Via Coeli to Archbishop Davis in August 1965 and to Fr. Temple in December 1965. He had three areas of complaint:

a. Solicitation of sex by guest-priests who were allowed to go into the area on temporary (weekend) parish assignments;

b. Alcohol and drug abuse by certain Paraclete members who were house superiors; and

c. The quality of the program.

Fr. John Feit was one of the superiors Fr. Murphy complained about. Feit submitted a response to Fr. Temple as did Fr. Gerald (Sept.30, 1966). Feit referred only to the quality of the program and made no mention of the other two points. Fr. Gerald claimed that any house superior who had abused alcohol was subsequently removed, and that at that time (1966) no superior had been intoxicated from alcohol or drugs in two and a half years. He defended the programs in place, but as to the accusation of guests soliciting sex he did not make any direct references. However, Fr. Feit's response made an oblique reference to serious misconduct, which probably referred to sexual misconduct since he had already confronted the alcohol/drug issue. His statement is an admission that in fact, such solicitation had happened: ·eIn isolated instances of serious misconduct the offending individual, when proven guilty, has been speedily dismissed from Via Coeli.”

The Murphy report was a significant element in the dispute over the direction of the community that lasted for two years.

Problems among the Paraclete Membership. There have been problems among the Paraclete membership. Several members had been guests there themselves. The most notorious is John Feit who had pleaded "no contest" to an abuse charge before he arrived at Via Coeli. Fr. Gerald admitted that Paracletes who were alcoholics had occasionally lapsed. The problem of alcoholic members who lapse has been recurrent over the years.

5. Fr. Gerald's Ministry Ends

The Island. Fr. Gerald had a very negative opinion of priests who sexually abused minors. In the 1950's he wrote to a number of bishops asking if they had an island in their dioceses where he could establish a totally isolated facility to permanently house such priests. Ironically, the bishop who responded was Archbishop Davis, then Archbishop of San Juan, Puerto Rico who had no idea he would soon succeed Archbishop Byrne. Archbishop Davis offered the island of Tortola but this was deemed unsuitable because it had several thousand inhabitants. In the early sixties the Paracletes established a facility on the island of Carriacou in the Diocese of Grenada. Fr. Gerald sent a down payment of $5000.00 as earnest money with a promise to pay the remaining $28,000.00 in future payments.

Archbishop Byrne died in 1963 and was succeeded by Archbishop Davis in early 1964. Fr. Gerald and Archbishop Davis did not share the close and supportive relationship that had existed with Archbishop Byrne. Fr. Gerald's total control of most aspects of the Paraclete ministry, the tangled finances, and the dispute over treatment modalities were the elements of a dispute that would last for two years.

Archbishop Davis ended the dispute with a series of decisions that would change the Paraclete community and the treatment they provided troubled priests.

The Archbishop sent a letter to Fr. Gerald on August 23, 1965. The letter contained eight "orders" that he was to carry out. He was to sell the island as soon as possible. He was to appoint Fr. William Tobin as superior of Via Coeli and Fr. McNamara as superior of the new foundation in Scotland. Finally, he ordered Fr. Gerald to accompany him to Rome for the fourth session of the Vatican Council. Fr. Gerald complied. This was the end of his authority. He never again resided at Via Coeli and although he retained the title of Servant General, he never regained the power he once had. Fr. Gerald died in Marlboro, MA on June 28, 1969 while giving a retreat. He was buried in the Paraclete cemetery in Jemez Springs on July 4, 1969.

6. Fr. Gerald and Clergy Child Molesters

Bishops and religious superiors were sending priests with sexual problems to the Paracletes at least from 1948 onward (cf. Letter of Fr. Gerald to a priest who had already been at the facility, 9-27-48). According to Fr. Gerald, half of the priests sent his way had alcohol problems and the other half had sexual problems. Concerning those with sexual problems, Fr. Gerald said that two out of five were cases of priests involved with women and three out of five were "aberrations involving homosexuality." (Letter of Fr. Gerald to Bishop Joseph Durick, 9-10-1964).

Fr. Gerald sent a number of letters to various bishops and religious superiors between 1948 and 1964 in which he made direct reference to priests who sexually abused minors. Although it is not known exactly how many such priests Fr. Gerald encountered in the early days it is clear that he did in fact try to provide treatment. In a letter to Bishop Dwyer of Reno, Sept. 12, 1952, he refers to the "handful of men we have seen in the last five years who have been under similar charges."

In several of his letters Fr. Gerald clearly stated that he would not welcome priests who had sexually abused minors (cf. letter sent to a priest whose name is redacted on 9-27-1948, "It is now a fixed policy of our house to refuse problem cases that involve abnormalities of sex."). There is no question that the "abnormalities" he refers to are sex with minors since in the same letter he speaks of the recipient's problem as "your intimacies with youth." He wrote to Archbishop Byrne to seek his concurrence with this policy on Sept. 18, 1957. Yet other letters clearly lead to the conclusion that Fr. Gerald, though reluctantly, took in priests with such psycho-sexual problems (cf. to Bishop Dwyer of Reno, 9-12-52; Bishop Brady of Manchester, 9-26-57; Bishop Primeau of Manchester, 6-30-61; Bishop Hines of Norwich, 5-7-63; Bishop Schenk of Duluth to all U.S. bishops, 1-28-66).

Fr. Gerald's Attitude. Fr. Gerald's attitude toward priests who had sexually abused minor boys or girls was clearly negative. He did not believe they could be cured and held out no hope that they could ever function in active ministry. He voiced the strong opinion to many bishops that such priests should be laicised, even if against their will. He held out an alternative to laicisation and that was permanent residence in a secluded location with no ministry and no contact with outsiders. As early as 1948 he spoke of finding an island where such priests could live out their lives "far apart from civilisation" (cf. letter, 9-27-48). Fr. Gerald had a clear and realistic understanding of the danger they posed, an understanding that may not have been widespread at the time but which certainly proved prophetic. His letter to Bishop Dwyer indicates that his opinions were shared by other bishops: "Many bishops believe that men are never free from the approximate danger once they have begun. Hence, leaving them on duty or wandering from diocese to diocese is contributing to scandal or at least to the proximate danger of scandal." He was especially harsh in his assessment in a letter to Archbishop Byrne, Sept. 18, 1957: "It is for this class of rattlesnake I have always wished an island retreat – but even an island is too good for these vipers of whom the gentle master said – it were better they had not been born.”

Warnings to Bishops. Fr. Gerald wrote to bishops and religious superiors about priest-sexual abusers for the duration of his time as Servant General. It is safe to assume that his advice to all bishops was the same as that found in the available letters. He warned bishops that they should bring about the laicisation of such priests, with or without their consent, because they would only continue to cause serious problems. In his letters he shows that his primary concern was not for the Church's image but for the children and the lay people.

7. Fr. Gerald and the Holy See

By 1959 it is clear that Fr. Gerald's work had come to the attention of the Holy See. On Sept. 14, 1959 he received a glowing letter of commendation from Pope John XXIII. In 1962, at the request of Cardinal Ottaviani, Prefect of the Holy Office, he submitted a report dealing exclusively with priests who sexually abuse minors. He urged that such priests "be given the alternative of a retired life within the protection of monastery walls or complete laicisation. We have the former in most cases, for laicisation is at best the less of two evils." (Letter to the Holy Office, April 11, 1962).

Pope John XXIII died on June 3, 1963 and Pope Paul VI was elected on June 21, 1963. Fr. Gerald had an audience with Pope Paul on August 26, at which he obviously discussed the problem of priest-abusers because the pope asked him for a report on "the problem of the problem priest." He refers to "sins with the young" and says to the pope, "Where there is indication of incorrigibility, because of the tremendous scandal given, I would most earnestly recommend total laicisation."

In a letter to Bishop Durick, Sept. 16, 1964, he refers to his audience: "I myself in an audience I was privileged to have with His Holiness, Pope Paul, and spoke of this matter which undoubtedly has been one of the deep concerns of his fatherly soul.”

Response to the Publication of Fr. Gerald's Letters. Fr. Gerald's letters including the two reports to the Holy Office and Pope Paul VI were unknown to the public until 2007 when they were unsealed by a judge. Fr. Gerald's consistent recommendations concerning clergy sexual abusers contradict one of the standard defences of the bishops in the U.S. and elsewhere: that they were unaware until recently that these men should not be put back in ministry. Several official Church sources attempted to discredit the importance of the letters. A spokesman for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles said that Pope Paul VI probably never saw the report submitted by Fr. Gerald even though it is clear that the Pope personally requested it.

A spokesperson for the Catholic Bishops Conference in the U.S. said "it [the documentation-the letters] shows certainly the insidiousness of the disease and it reinforces current church policy." This is a strange response since the letters were written at a time when the church policy was to place such men back in ministry in spite of Fr. Gerald's clear warnings. The spokesperson, Sr. Mary Ann Walsh, went on to defend the bishops by claiming they tried to do the right thing "·cby taking the advice of the psychological and medical community." This too is strange because Fr. Gerald was the bishops' primary resource for help with troubled priests and a man whom they consistently supported financially and whose expertise they honoured.

Bishop Blaise Cupich said in a phone interview that "his views, by and large, were considered bizarre with regard to not treating people medically but only spiritually·cThere was mounting evidence in the world of psychology that indicated that when medical treatment is given these people can, in fact, go back to ministry." While it is true that by the mid-sixties there was disagreement among the Paracletes about Fr. Gerald's exclusively spiritual methods of rehabilitation, there is no evidence from the documentation that his views on sexually abusive priests were considered bizarre. Fr. Lechner, the current Servant General, wrote an article in their monthly publication Priestly People in which he referred to Fr. Gerald's policies. He described his opinions about priests who molest minors without critical comment and went on to state that the criticism of Fr. Gerald was directed at the fact that his treatment programs were strictly spiritual ("A Crisis in the Church," Priestly People, 2002). The responses Fr. Gerald received from several bishops clearly attest to their understanding of the grave nature of the problem. More important is the fact that Fr. Gerald was sought out by the Vatican for his views on the problem.

Fr. Gerald urged that any priest who sexually abused a minor be laicised even if against his will. No bishop to whom he made this suggestion ever initiated a process for laicisation. The Holy See did not act on his urgent suggestion either. There are clear reasons for this lack of response. During this period, voluntary laicisation that was requested by the priest himself was extremely rare, and imposed laicisation against the priest's will was non-existent. There is one known case of involuntary laicisation during the papacy of Pope Paul VI and none thereafter until 1998, when Pope John Paul II agreed to the involuntary laicisation of several priests from Boston. The priesthood was considered so sacred a calling that the popes and the Vatican curia considered the concept of taking it away from a man to be an abhorrent violation of his right to remain a priest, no matter what he had done. Consequently it is understandable why Fr. Gerald's solution was never acted upon.

8. Treatment Programs

During Fr. Gerald's tenure as Servant General the Paraclete facilities were officially known as retreat houses and not as therapeutic centers. Fr. Gerald's concept of rehabilitation was totally focused on spiritual rehabilitation.

Archbishop Davis mandated that the Paracletes incorporate Alcoholics Anonymous as well as psychotherapy and psychiatric counselling in 1966. Fr. Gerald's influence and control waned, and the Paraclete mission evolved from exclusive spiritual renewal to holistic spiritual renewal which included secular forms of treatment.

In 1976 Frs. William Perri and Michael Foley started a treatment program for priests with psycho-sexual problems. They borrowed from programs used at sexual disorders clinics in secular settings. These included psychotherapy, education in human sexuality, and in some cases chemical therapy using depo-provera.

9. Treating Sexual Problems

Fr. Gerald believed that sexual problems were essentially moral problems. However in one letter to Bishop Brady of Manchester, NH, he said "From our experience with characters of this type, and without passing judgment on the individual, most of these men would be clinically classified as schizophrenic. Their repentance and amendment is superficial." (9-26-1957). Nevertheless his method of treatment was totally spiritual. He did not believe that priests who sexually abuse minors could be cured or even controlled to the point where they could return to some form of ministry. He agreed to take such men at the Paraclete facilities not for treatment but for supervised, permanent residence. He envisioned such situations as a kind of life-long penance whereby these priests were isolated from the public and could not do harm to the Church.

The Servants did not actually begin attempts at treating priests with sexual problems until they adopted the program proposed by Dr. John Salazar in the late sixties. In his affidavit Fr. McNamara said that prior to this program if the Servants discovered that a guest-priest was sexually attracted to males he was asked to leave immediately. This refers to the period after Fr. Gerald lost power and the start of Salazar's program. Fr. McNamara also confirmed that in the mid to late sixties the Paraclete fathers "received a number of inquiries about accepting priests who had been accused of molesting children." (Affidavit, par. 32).

Frs. Michael Foley and William Perri were sent for specialised training so that they might deal with psycho-sexual issues. They founded a program in 1976 that remained in place for 19 years. This program was exclusively for priests with sexual problems. The Paracletes and Dr. Jay Feierman have reported treating over 600 priests in this program during its existence (cf. Sipe Report, 6-12-2006). This number was confirmed by a source from the Institute for Living in Hartford CT in a Boston Globe article, July 19, 1992 (James L. Franklin, Ways cited to treat priests who abuse).

In a New York Times article, Dr. Feierman was quoted as saying, "By the mid-1980's when the case of a Louisiana priest, Rev. Gilbert Gauthe, brought the problem to public view, the Paracletes had already treated hundreds of clergymen who had molested minors." (Erica Goode, "Abusive Priests Are Varied, but Treatable, center Found," New York Times 4-26-2002).

The Gauthe case from Lafayette, Louisiana brought the hidden problem of clergy sexual abuse into the public forum in 1984 and 1985. The second major wave of revelations began in 2002 with the investigative series published by the Boston Globe. Catholic bishops in the U.S., both individually and as a group, regularly claimed that they had not appreciated the serious nature of sexual molestation of minors. Many claimed it was a new phenomenon and that they were on a steep learning curve. The information that the Paracletes had already treated "hundreds" by 1985 refutes these defenses.

Dr. Feierman's Study. Jay Feierman conducted a study of 238 priests who were treated for sexual problems at Via Coeli between 1982 and 1991. According to the New York Times (Erica Goode, April 26, 2002), this study was accepted for publication in the professional journal, Archives of Sexual Behaviour. Fr. Peter Lechner, the new director of the program, asked him to withdraw the manuscript and told him not to discuss the findings in more detail.

10. Termination of Treatment Programs for Sexual Abusers

Beginning in March 1992 a series of lawsuits were filed which named the Servants of the Paraclete and their treatment facilities as defendants. These lawsuits came about because several priests who had been treated by the Paracletes had sexually abused minors while still in treatment and others had abused minors after having been released and placed back in ministry. Four of the more notorious and prolific sexual priest-predators were Fr. James Porter, who first went to Via Coeli in 1967; Fr. Jason Sigler, who first went to Via Coeli in 1970, returning in 1978 and again in 1981; Fr. David Holley, who first went to the Paracletes in 1971 and is now imprisoned; and Fr. Rudy Kos, who left the Paracletes in 1993 and was convicted and sentenced to life in prison in 1998.

The Paracletes responded to the suits and the critical publicity by drawing attention to the pioneering work they did in the mid-sixties with alcohol treatment programs and programs for priests with psychological problems. It is true that the Paracletes were in the forefront of both acknowledging and providing treatment for the emotional and psychological problems facing priests. The official Church was very reluctant to admit to the existence of alcoholism and psycho-sexual problems among both diocesan and religious order priests. Substance abuse and addiction as well as sex-related problems were believed to be moral issues by Church leaders, from the Vatican on down to the local bishops. The solution to such problems was a combination of spiritual exercises, training the will, and doing penance. Many bishops were exposed to the advances in the behavioural sciences about alcoholism and psychological and sexual disorders, yet there was no uniform acceptance of these advances and of the professional modalities of treatment that were being developed. In spite of his conviction that alcoholism and certain emotional/psychological problems were conditions that could be solved with heavy doses of spiritual practices, Fr. Gerald was ahead of his time in that he acknowledged the existence of such problems and, rather than bury them in denial, he sought to find ways for renewal and recovery. His insistence on resorting to spiritual exercises, especially devotion to the Eucharist, is understandable though anachronistic. Nevertheless it must be said in his favour that he obeyed Archbishop Davis' orders and eventually cooperated with the introduction of contemporary secular methods of treatment.

The Paraclete's response to the lawsuits in the 1990's was in line with the general responses given by individual bishops as well as the Bishops' conferences of the U.S., Canada and Ireland. The assertion was that little or nothing was known about psycho-sexual problems and disorders prior to the 1980's and 1990's. The official Church leadership claimed that they were following the direction and advice of psychologists and psychiatrists who told them that men with these disorders could be cured and returned to ministry.

Church leaders also claimed that the social awareness of the serious nature of pedophilia and ephebophilia – that is, sexual attraction to pre-pubescent children and to younger adolescents, respectively – was much different than in the 1980's and 1990's. They were led to this belief in great part by the work of Professor Philip Jenkins, a professor of religious studies and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He published his first book, Priests and Pedophiles in 1996. The basis of his research is secular media stories that reflect the cultural response to these sexual disorders in past decades. Among other things he claims that anti-Catholic bigotry among the secular media has been a major factor in sensationalising the problem in the Catholic Church. He has written other articles with the same basic themes and has testified as a defence expert witness in several cases in the U.S. His standard defence for the Bishops' response to reports of sex abuse by clergy is that the bishops followed the standards recommended by the best secular expert opinion prevailing at the time. In one of his expert reports he said: "One significant contrast to modern attitudes was that in the 1956-76 era, child sexual abuse was not regarded as a grave or pressing problem, and accordingly it attracted little attention in terms of publications, whether secular or popular·c.Reacting against the panic atmosphere of earlier years, the consensus of expert opinion in the 1956-76 era held that: *while molestation and sexual abuse occurred, it was not necessarily serious or devastating in its effects, *The degree of harm depended largely on the official response to a complaint. Heavy-handed actions by police and/or courts were likely to traumatise a child." In another place he claimed that sexual abuse of children was considered "trivial" during this era.

This is not the forum for a detailed refutation of Jenkins' theories, however, it is safe to say that they are not supported by other areas of scholarship that have examined the question of sexual abuse of minors by adults, clergy or otherwise. One salient point: if child sexual abuse was considered by society to be "not necessarily serious" between the 1950's and the end of the 1970's this does not explain the criminal justice system in the U.S., which uniformly considered sexual molestation to be a serious felony.

Guest-Priests in local parish ministry. Fr. Gerald allowed guest-priests to work in local parishes on weekends. His letter to a guest-priest who had left (9-27-48) reveals that the priest had acted out while working in a local parish and was therefore not allowed to return to the Paracletes. In his 1966 report Fr. Murphy's first complaint was that a priest had acted out in his parish (Assumption). He reported this to the superior (Fr. Moylan) and says "·she disclaimed all responsibility for the conduct of guest priests in relation to the civil community." Fr. Feit did not mention this complaint in his written response but Fr. Gerald, in his response, acknowledged that there had been problems of this nature: "In isolated instances of serious misconduct the offending individual, when proven guilty, has been speedily dismissed from Via Coeli.

The practice of allowing guest-priests to work in local parishes was discussed by Archbishop Davis and the staff, including Dr. Salazar, at a meeting on Feb. 13, 1967. It was generally agreed that priests could work in local parishes with the approval of the Paraclete superior and the Archbishop. The notes state that even priests in a therapeutic relationship with Dr. Salazar would be allowed to do such work. Archbishop Davis said that he would take it upon himself to use his judgment and discretion "in informing pastors only of what he thought they must absolutely know about the priest they were receiving."

In the 1990's the Paracletes were named in over 40 civil suits, based on multiple cases of sexual abuse of minors by guest-priests whom the Paracletes allowed to work in local parishes. The Paraclete's general defence was that their psychologists and psychiatrists believed that after treatment some priests can safely return to public ministry, based on the theory that they could be cured of their problem. In his affidavit Fr. McNamara said: "...I am told by experts today that psychologists and psychiatrists in the 60's and 70's had views and opinions on treatment and cure of pedophiles which are no longer held by experts."

Fr. McNamara claimed that the psychologists and psychiatrists came up with the idea of sending priests with psychosexual difficulties to do parish work (affidavit, par. 34) yet the 1967 record of the meeting cited above clearly shows that the practice had been in place and was supported by the Paracletes and the archbishop.

Dr. Salazar was deposed on March 10, 1993 in conjunction with the lawsuits. He testified that in fact, he had told the Paracletes not to allow priests with psychosexual difficulties to do outside parish work.

One of the most damning confirmations of the practice of allowing sexual abusers to work in parishes is found in an affidavit of David Holley, sworn to on May 14, 1993 at the prison where he is incarcerated. Holley admitted that his disorder began to manifest itself in 1962, four years after ordination. In 1968, his bishop (Bernard Flanagan) sent him to Fr. Jerome Hayden, a psychiatrist because he had been molesting boys. He was sent to Seton Psychiatric Institute in 1969 for the same reason. In September 1971 he was sent to the Paracletes in New Mexico. Upon arrival he was taken to a Paraclete house in Albuquerque and never went to the Jemez facility. Of his time with the Paracletes he says: "I was never given a psychiatric or psychological evaluation or a spiritual evaluation. No history of my problem was taken. I participated in no therapy or treatment programs offered by the Paracletes. I never met with a Paraclete psychiatrist or psychologist·c.Almost immediately after I arrived at Paraclete I was given a parish assignment for weekend work in the South Valley of Albuquerque." (Affidavit, par. 11).

The Paracletes have claimed a very low recidivism rate among the priests they have treated. Fr. McNamara stated that "To this day [1993] I don't know of a single case in which a priest who participated in the program called the "module" which began in 1977 was recommended for a return to ministry involving children and later had a complaint made against him." (Affidavit. par. 40). In 1986 Dr. Feierman said in a report to the Diocese of Beaumont that "our recidivism rate for behavior which would be considered criminal is zero percent to the best of our knowledge." (Letter to Rev. Michael Jamail, 5-16-1986) In 2002 he was quoted by the New York Times (Erica Goode, 4-26-2002) saying that he knew of only two men who were later arrested for sexual abuse and perhaps 5 or 10 more who were caught in suspicions circumstances. In the same article Fr. Lechner claims that he did a study in 1992 of 89 men treated and that only one had lapsed.

Since 1985 there have been several thousand civil cases prompted by clergy sexual abuse in the U.S. No detailed study has been made of the files produced in these cases. Nevertheless there is documentation confirming that a significant number of perpetrators had been treated or were resident at the Paraclete facilities prior to abusing minors. Upon inquiry several of the attorneys who have represented victims have provided the names of perpetrating priests who had been in treatment at a Paraclete facility before they sexually abused their clients. The following is a list of the names, which is probably incomplete:

James O'Malley, Spokane, WA

William Wood, Yakima WA

Brian Gallagher, Yakima WA

James McGreal, Seattle, WA

Christian Anderson, Orange, CA

John Salazar, Amarillo TX

John Quinn

Bruce MacArthur, Sioux Falls SD

Michael Baker, Los Angeles, CA

Earl Bierman, Covington KY

David Holley, Worcester MA

Carmine Sita, Jefferson City, MO

Denis Lyons, Orange CA

James Poole, SJ (Jesuit Province of Oregon)

Albert Wilwerding, Des Moines, IA

Michael Wempe, Los Angeles, CA

Patrick McCabe, Ireland

Edward Rodrigue, San Diego CA

John T. Sullivan, Manchester NH

William Allison, Fresno CA

Edmund Boyle, Reno NV and Portland OR

Bernard Bissonette, Norwich CT

Lawrence Brett, Hartford, CT

Art Perreault, Hartford, CT

Robert Smith, Springfield, MA

James Porter, Fall River MA

Jason Sigler, Winnepeg SK

Mel Balthazar, Philippines, Cleveland OH

Franklin Becker, Milwaukee WI

Franz Robier, San Diego CA

Robert Nikilborc, San Diego, CA

Javiera Gutierrez, Juneau, AK

Eddie Gilbin, New York, NY

Romano Ferraro, St. Louis, MO

Robert Yim, St. Louis, MO

11. Document Destruction

Fr. Gerald did not send regular reports to bishops or religious superiors. Since his "treatment" program was spiritual in nature most, if not all, individual sharing between Paraclete fathers and the guest-priests would have been considered privileged information. Nevertheless he wrote to bishops about guest-priests when he saw a need to do so. Copies of a number of his letters were among the Paraclete files unsealed in 2007.

One of Fr. John Murphy's complaints in 1966 concerned the lack of written reports. Fr. Feit responded that periodic reports were sent to bishops and religious superior though not on a regular basis. After 1967 psychologists and psychiatrists were involved in the assessment and treatment of guest-priests. It is safe to assume that these medical professionals made written notes of the results of evaluation and testing and progress notes in the course of a therapeutic relationship.

In July 1968 Fr. Feit announced that the superior and staff of Via Coeli would commence the practice of sending bishops and religious superiors monthly reports on the guest-priests. These reports followed a standard form and included a brief summary of the guest's status in the following areas: spiritual, physical, social, and therapy, with a section for additional remarks.

By the beginning of 1989 the Paracletes had a document destruction policy in place. When reports were sent to bishops or religious superiors they were asked to either destroy them or return them to the Paracletes for disposal (cf. Letter from Liam Hoare to Bishop Thomas O'Brien, 2-22-1989). Most if not all of the treatment records and related information for guest-priests who had been treated in the special treatment program called "The Module" had been destroyed by 1990.

12. A Case Study: Fr. Francis Markey of the Diocese of Clogher in Ireland

Francis Markey was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Clogher in Ireland in 1952. Bishop Eugene O'Callaghan was bishop at the time of his ordination until 1969 when he retired. He was responsible for Markey when he first abused in 1964. The diocese has territory in the Republic but also has territory in the north. Markey was discovered to have sexually abused a child in 1964 and was sent for treatment at St. John of God psychiatric hospital in Stillorgan, a southeast suburb of Dublin. After a period of residential treatment he was reinstated as a parish priest back in his diocese.

Markey was accused again in 1973 and again was suspended and sent to St. John of God Hospital. He was reinstated after treatment and accused again in 1974. At this time Bishop Paul Mulligan (1969-1979) was the bishop. Fr. Markey was sent not to St. John of God but to Our Lady of Victory Treatment Centre, a facility run by the Servants of the Paraclete in Stroud, Gloucestershire, England. Markey was assigned there on a temporary basis between 1976 and 1981. In 1981 he was sent to the Paraclete facility in Jemez Springs, NM. In 1982, while remaining officially incardinated to Clogher, Markey was assigned to live and work in the diocese of New Ulm, MN. The bishop of New Ulm knew that Markey had previously received treatment at the Paraclete facility for sexual disorders. Bishop John Duffy was bishop at this time (1979-2010).

No one from the Paracletes, the Diocese of Clogher or the Diocese of New Ulm ever informed the people of the parish where Markey worked that he had been in treatment for sexual problems and moreover, that he had been suspended from ministry at least three times.

In 1982 Markey was working at St. Andrew Parish in Granite Falls MN when he sexually abused an 8 year-old minor. The bishops of both dioceses and the superiors at the Paraclete facilities in England and New Mexico who had provided treatment all knew of the great risk taken in allowing Markey back into active ministry. Thus far he had been in treatment twice in Ireland and had reoffended at least three times after having been in a residential facility.

Knowing of Markey's extensive history of abuse and treatment, the Paracletes allowed him to become a member of their community in 1984.

The Servants of the Paraclete had an inconsistent policy with regard to their post-treatment recommendations for priests who sexually abused minors. As has been seen in section 6, above, Fr. Gerald, the Servant General between 1947 and his death in 1969, was adamantly opposed to allowing priests who sexually abused minors to remain in any form of ministry. So great was his fear that they would relapse, that he urged not only bishops and religious superiors, but Vatican officials and the Pope himself that for the good of the Church, such men should be laicised even against their will. When he realised that this would not happen he adapted his policy and allowed such priests to live at a Paraclete facility. It was clear from his writings, however, that he held out no hope for successful therapy and saw the Paracletes as providing secluded custodial care in a setting where these priests would be far removed from any lay population.

After Fr. Gerald's death the policy changed. The Paracletes, with the approval of Archbishop Davis of Santa Fe and against the advice of their own psychiatrist, allowed priests with psycho-sexual disorders to work in local parishes. The Archbishop stated at a staff meeting in 1967 that he would take it upon himself to inform pastors of the various priests' conditions, but only in very rare circumstances. It is obvious that this policy continued through the years. The Paraclete's treatment program for priest with sexual disorders was closed down in 1995 precisely because of lawsuits that were filed on behalf of people who had been sexually abused by guest-priests from the Paracletes either in the local area or elsewhere.

The Paracletes regularly recommended that priests whom they had treated be reinstated in ministry. This was directly opposed to Fr. Gerald's policy. Although some have raised the opinion that Fr. Gerald was a lone voice with bizarre ideas, his predictions proved true in many cases. Bishops who refused to heed his advice later had to deal with priests who re-offended.

Although the Paracletes have claimed several times that only a very small number of their "graduates" ever lapsed or re-offended, the actual experience in many dioceses has shown the opposite to be true. At the end of section 10 there is a list of 34 priests who offended at least once after treatment from the Paracletes. This list is not complete.

Our Lady of Victory Treatment Centre at Stroud was opened in 1959. Some 1800 priests and religious men are thought to have been treated there. ("Acts of Contrition" Guardian.co.uk, Nov.10, 2004). According to another media report: "Our Lady of Victory purports to offer 'therapy in a spiritual context,' " ("Gay priest reveals secret of Catholic 'boot camp' " The Independent Aug. 27, 1997).

Our Lady of Victory became well-known in the U.K. in 1993 when Fr. Sean Seddon, a 38 year-old priest, was sent there after having a sexual relationship with a teacher. Upon learning that the teacher had lost their baby, Fr. Seddon committed suicide by throwing himself under an on-coming train at a railway station near the facility.

As of 1997, most of the residents were alcoholics in the chemical dependency program; however, there were also priests who had sexually abused children. According the report in The Independent, a representative of the Catholic Media office said, "In the case of child abuse it would be assessment rather than treatment because most people realise that paedophilia is not a condition they can treat successfully." Some of the priests who underwent treatment for child abuse had served prison sentences. At the end of the treatment, the staff at Stroud assessed the paedophiliac priest's risk of reoffending and then the priest was assigned to a job that was appropriate for the risk.

In 1998, Our Lady of Victory was plagued with problems. Three of the eleven core staff, including clinical director Fr. John Murphy, resigned and left. Rumours of improper sexual relationships between staff and clients were rampant ("Clinic shuts its doors to sex-abuse priests " The Independent, April 1, 1998). Consequently, according to Fr. Liam Hoare, the Servant General at the time, Our Lady of Victory had decided to stop treating priests with sexual abuse issues "because of the sensationalism surrounding such issues." Fr. Hoare also admitted that Our Lady of Victory was being closed because it did not have the required skills to deal with high risk cases. It appears that he was referring to child sexual abuse cases.

That same year, the Paracletes announced that the centre would close. Although it was not stated, the closure coincided with the pattern of closures that had started in the mid-nineties due to the lawsuits filed against the Paracletes in the U.S. In spite of the prediction that the facility would close in 1998, it remained open until December 2004 (cf. "Acts of Contrition," www.guardian.co.uk , Nov. 10, 2004)

Paraclete Report

January 11, 2011

Overview

The Servants of the Paraclete is the name of a Roman Catholic religious community of men. The community was founded in 1947 by Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald under the original patronage of Archbishop Edwin Byrne, Archbishop of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The name of the community includes the word "Paraclete" which is derived from a Greek word meaning "advocate" or "helper." This word is also used to describe the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit.

The community was founded for the sole purpose of providing assistance to priests with substance abuse or psycho-sexual problems. The original foundations were in New Mexico. In time the community opened houses in several other States and in foreign countries including the U.K. The Paraclete community provided treatment to priests who had sexually abused minors from its inception in 1947. In the 1990's it was faced with a series of lawsuits, all related to priests who had been treated by the community for sexual abuse of minors. By the end of the decade the Paracletes had ended their ministry to priests who had committed sexual abuse of minors, at least in the U.S. The Paraclete facility in the U.K., Our Lady of Victory Treatment Centre at Stroud, continued to treat sexually abusive priests until it closed in 2004.

Since the mid 1980's there has been controversy over the treatment methods used by the community and over the suitability and stability of certain of the Paraclete members themselves. The controversy began when it was revealed that certain guest-priests who had been serving on a temporary basis in local parishes had sexually abused minors while in treatment or had abused minors after completing treatment. This led to criticism of the treatment methods, supervision, and quality and effectiveness of after-care programs.

1. Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald and the Foundation of the Servants of the Paraclete

Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald was born in Boston in 1894. He was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Boston in 1921. He served in Boston area parishes until 1933 when he received permission to join the Congregation of the Holy Cross, a world-wide religious community. He was made rector of a college-level seminary for the community, and while in that assignment he developed the idea of founding a religious community of men who would serve troubled priests.

The Servants of the Paraclete, as the order is formally known, was originally an official religious community under the sponsorship and authority of the Archbishop of Santa Fe, New Mexico in the U.S. Although it had existed since 1947 it achieved its first level of official status in 1952. As the community expanded and as its mission became known not only in the U.S. but in Europe as well, the superiors petitioned the Holy See to be granted Pontifical Right status. This means that the community would be placed under the authority of the Pope. The decree granting this status was issued on Jan. 16, 1971.

Fr. Gerald circulated a request for support among Catholic bishops and received a favourable response from Archbishop Edwin Byrne of Santa Fe. With financial help from Cardinal Spellman of New York ($25,000), Fr. Gerald purchased 2000 acres near Jemez Springs, NM and set up his first foundation in a former Franciscan monastery. In the early decades the Paraclete facilities were not identified as treatment facilities but as retreat houses (cf. Affidavit of Fr. Joseph McNamara, Nov. 17, 1993, par. 5). Fr. Gerald was an intensely spiritual man with a high regard for the priesthood as an exalted and mystical calling. He firmly believed that the best treatment for the problems of the priests who sought his help or were sent to him by their bishops was a concentrated spiritual program. To achieve this end the guest-priests, as they were called, were obliged to participate in various spiritual exercises such as Mass, spiritual reading, meditation, common prayer, private prayer and periods of silent prayer and reflection before the Blessed Sacrament. The spiritual program consisted mostly of formal exercises arranged throughout the day in such a way that the guests had no time periods of more than four hours for any other type of activity.

Expansion. Fr. Gerald wrote to numerous U.S. bishops describing his goal of creating a retreat centre specifically for the renewal of priests with sexual and alcohol problems. Since there was no such resource in the U.S. at the time of the Paraclete foundation, the bishops generally responded favourably. Fr. Gerald was providing a resource that answered an obvious need. In 1950 Fr. Gerald wrote to Bishop Buddy of San Diego and told him that for the first time in the community's three year history the main monastery, known as Via Coeli (Way to Heaven) was filled to capacity and had to turn a priest away. He went on to state that at that time there were priests from 35 U.S. dioceses and 9 religious communities at Via Coeli.

There have been five general superiors of the order, known as Servants General: Fr. Gerald Fitzgerald, 1947-1969; Fr. Joseph McNamara, 1969-1981; Fr. Michael Foley, 1981-1987; Fr. Liam Hoare, 1987-1999; and Fr. Peter Lechner, 1999 to the present.

When the Servants received their first official status as a diocesan community in 1952 there were 17 members. The peak year for membership was 1968 with 112 members. The first period of decline was between 1971 and 1991 when membership decreased from 80 to 42 during that twenty year period. The second period began in 1992 when membership declined from 33 to 22 in 2002 (All statistics taken from the Official Catholic Directory between 1953 and 2002). If the Paraclete website reflects the current numbers, the community now comprises 15 priests.

The Paraclete mission rapidly expanded from the time of its foundation. The first facility and Paraclete community was in Jemez Springs, NM. In time Fr. Gerald opened a house in Albuquerque, the "Albuquerque Villa." The expansion went beyond U.S. borders:

1947: Jemez Springs, NM

1956: Santa Fe, NM; Neves, MN; Gallup NM; San Diego, CA

1958: Burlington, VT; Youngstown, OH

1961: British Virgin Islands; Stroud, England

1962: Rome, Italy; Santa Cruz, Mexico; Rapid City, IA; Chicago, IL

1965: Two houses in South America, one in Africa

1966: Dumfriesshire, Scotland

1967: Jallais, France

1971: San Bernardino, CA; St. Louis, MO

Decline. The Paracletes faced lawsuits and media scrutiny in the mid 1990's based initially on extensive sexual abuse by priests who had been guests at the Paracletes, notably Fr. James Porter, Fr. Jay Sigler and Fr. David Holley. The community terminated its treatment programs for priests with psycho-sexual disorders and began to close many of their houses. At the present time, the Paracletes list houses in Dittmer, MO., Albuquerque, NM and Tagayta City, Philippines. The order closed its house, Our Lady of Victory, in Stroud, England around 2004. There is a current listing for Our Lady of Victory Trust in Stroud, but it is uncertain if this is a Paraclete facility.

2. Professional Qualifications of Paraclete Members

The early members of the Paraclete community included men already ordained and assigned to other dioceses or religious communities. Like Fr. Gerald, they sought permission to transfer to the new community in great part because of the unique nature of the work. None of the early members, including Fr. Gerald himself, had professional credentials or training of any kind that would have aided in helping priests with alcohol or psychological problems. If a guest needed or wanted psychological or psychiatric help, he was referred to resources in the surrounding area.

Fr. Gerald wrote a report dated Sept. 30, 1966, in which he summed up the training program for members of the Paraclete community: "There IS a training program for Paracletes. It is a very fine and wide-spread kind of program: on-the-job training." He went on to state that the candidates for membership who were not yet ordained were trained in a program that "conforms to the standards which Mother Church has set up for the training of prospective priests." In 1967 following an internal dispute fueled by a highly critical report of Fr. John Murphy, the first two Paracletes were sent for professional training in psychology specialising in sexual deviation (cf. Richard Sipe Report, May 3, 2006)

A number of guest-priests who had received treatment at one of the Paraclete facilities in time became members of the community. There is no documentary evidence that any of these priests ever received specialised training in psychology or a related area, although it is entirely possible that some did receive such training. Among the guest priests who in time became either members of the Paraclete community or who became staff members at a Paraclete facility, there were several who had been confirmed as sexual abusers of minors.

Among the confirmed sexual abusers who have worked at the Paraclete therapeutic facilities have been:

a. Francis Luddy, Diocese of Allentown. Luddy admitted to abusing at least 5 minor boys. A civil trial in 1994 ended with an award of $1.5 million to two victims. Luddy went to the Paraclete facility in New Mexico for treatment and moved on to a position as administrative assistant and director of admissions.

b. Lane Fontenot, Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. Fontenot was convicted in 1986 and sentenced to a year in jail and two years treatment with the Paracletes. At least as late as 1994 he was still with the Paracletes and employed in an administrative position. (I have personal knowledge of his situation in 1994 insofar as his counselor, the late Fr. Michael Mack, was an acquaintance who had called me for canonical advice for Fontenot.)

c. John Feit, formerly a priest of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, then a member of the Paracletes. Feit pleaded no contest to aggravated assault in the attempted rape of a young woman in Edinburgh, Texas. Shortly after this assault he became a prime suspect in the murder of another young woman. In the 1960's he went to the Paracletes and subsequently became not only a member but a superior of one of their facilities.

d. Gordon MacRae, Diocese of Manchester, NH. MacRae pleaded guilty in 1988 to a sexual abuse charge and was sent to a Paraclete facility, Foundation House, in New Mexico. In 1990 he took a position there as assistant director. In 1994 he was convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to prison for 33 to 67 years.

John Feit had the opportunity to have the most significant impact on guest priests because of his leadership position. In 1972 he left the Paraclete community and subsequently married. He wrote reports in response to the charges made by Fr. John Murphy (see below) but most important, he was instrumental in returning Fr. James Porter to active ministry. Porter was credibly accused of sexually abusing many minor boys while serving as a priest in the Fall River Diocese. He was sent to the Paraclete facility in 1967, and while he was there John Feit was directly instrumental in allowing Porter to have weekend ministry assignments in New Mexico, where he abused more minors. Feit helped him find assignments in New Mexico, Texas and finally in Minnesota.

3. Internal Dispute over Treatment Modalities

Archbishop Edwin Byrne of Santa Fe was a staunch supporter of Fr. Gerald and was often referred to by Fr. Gerald as the "co-founder" of the Paracletes. As long as Byrne was Archbishop, Fr. Gerald had un-challenged control over the programs implemented by the Paracletes, which programs were completely spiritual in nature. Archbishop Byrne died on July 26, 1963 and was succeeded by Archbishop James Peter Davis, who had been the Archbishop of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Davis was appointed on Jan. 3, 1964 and resigned in 1974. In 1960 Fr. Gerald purchased a facility on an island in the Caribbean. He had originally been offered the island of Tortola by Archbishop Davis, then of San Juan. This venture did not work out and the Paraclete fathers then moved to the island of Carriacou. (The island episode will be covered below.) In 1965 Archbishop Davis ordered Fr. Gerald to sell the island (cf. letter of Archbishop Davis, 8-23-1965). An internal dispute coincided with the issue of the island. The dispute was over Fr. Gerald's control of the workings of the Paraclete ministries, his problems with administration and his reluctance and refusal to admit any type of psychological or psychiatric therapy programs. He distrusted any therapy programs and also distrusted Alcoholics Anonymous, refusing to allow such programs to be utilised as long as he had full charge.

Fr. Gerald's Approach is Challenged. Archbishop Davis began asserting more oversight and control over Fr. Gerald not long after he came to power in Santa Fe. During this period some of the Paraclete priests, notably Fr. William Tobin, superior of the community in Scotland, wanted to discuss other types of programs for the guest-priests, especially Alcoholics Anonymous. Fr. Gerald admitted that AA had helped many but he opposed it because it because it accepted the disease concept of alcoholism, a concept that was relatively new in the early 1960's even though it had been officially declared an illness by the American Medical Association in 1956. He believed that alcoholism was a moral weakness and could be "cured" by spiritual means (cf. letter of Fr. Gerald to Fr. William Kenneally, July 21, 1960).

Although Fr. Gerald would not interfere if a guest wanted to see a psychologist or psychiatrist, he would not require or even encourage this. His philosophy in this regard was supported by other members of the community, including Fr. John Feit. Both Frs. Gerald and Feit referred to the guests' problems as "weaknesses." Fr. Gerald said in a 1966 report that "psychiatric examinations for Paracletes have not been deemed necessary." Concerning therapy programs he said in the same report: "Insistence on mandatory therapy goes against the freedom and dignity of the human person as well as against acknowledged psycho-therapeutic techniques." (Report, Sept. 30, 1966).

The Vatican appointed Fr. David Temple, a Franciscan priest, to act as a "religious assistant" to the Paracletes to assist them in resolving their internal disputes. According to Fr. Joseph McNamara, Fr. Temple was to "serve as a brake on Father Gerald attempting to regain power in the United States." (cf. Affidavit, par. 28)

Fr. Bill Tobin, mentioned above, intended to bring up the matter of AA at the 1964 General Chapter, the general legislative meeting of the entire Paraclete order that took place every six years. Fr. Gerald heard of this and obtained permission from the Holy See to hold the Chapter by mail, which is how it was conducted. AA was not brought up and Fr. Gerald was re-elected as superior general of the order.

AA – The first professional program. Most of the guest-priests treated by the Paraclete community in the early years (prior to 1965) were there because of alcoholism or alcohol abuse. Fr. Gerald, in a letter to Bishop Durick of Nashville dated Sept. 10, 1964, said that one half of the priests treated were there for alcoholism. Archbishop Davis appointed Fr. Joseph McNamara superior of Via Coeli in August 1965 with instructions to implement lay therapy programs for the guest-priests (cf. Affidavit of Fr. McNamara, 11-17-1993, par. 20). Fr. McNamara set about implementing these instructions beginning with a program for treatment of alcoholics. He became convinced of the effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous and sent a request to Archbishop Davis that he be able to bring AA to Via Coeli and also hire a professional to run an alcohol rehab program that would supplement the AA program. Archbishop Davis agreed to both proposals. Fr. Gerald then tried to have the Archbishop remove Fr. McNamara as superior of Via Coeli, but this was refused by the Archbishop.

Fr. Gerald took the issue to the Congregation for Religious at the Vatican. The Congregation backed Archbishop Davis and supported his plan to involve AA as well as other lay therapy programs (cf. Ibid. par. 26).

The Participation of Psychologists. Fr. Joseph McNamara was appointed superior at Via Coeli in 1965. He hired Dr. John Salazar in 1966 as the first resident psychologist for the Paraclete programs. Dr. Salazar had first seen a Paraclete guest for evaluation in 1963 (cf. Deposition of Dr. John Salazar). Fr. McNamara also initiated other therapy programs in keeping with the orders of Archbishop Davis. The shift from a program based exclusively on traditional Catholic spiritual practices to a program described by Fr. Liam Hoare as a "holistic approach to our mission of spiritual rehabilitation" began in 1967 (cf. Affidavit of Liam Hoare, 3-23-1992, par. 22-23). This approach included spiritual, psychiatric and psychological counselling. The Paracletes contracted with psychologists and psychiatrists to provide the needed care and to assist in assessments and creation of treatment and after-care programs.

Dr. John Salazar was the first psychologist to work at the Jemez Springs facility on a permanent basis. Dr. Jay Feierman, M.D. was a consultant to the program between 1976 and 1995. Other psychologists who have worked at the facility have included Dr. Robert Goodkind, Dr. Sarah Brennan and two Paraclete priests, Fr. Michael Foley and Fr. William Perri.

4. Early Complaints – Fr. John Murphy's Report

The Holy See appointed Fr. David Temple as "Religious assistant" to the Paracletes in 1965. Fr. John Murphy, a priest from the Diocese of Lincoln, NE who had joined the Paracletes, sent a report critical of the conditions at Via Coeli to Archbishop Davis in August 1965 and to Fr. Temple in December 1965. He had three areas of complaint:

a. Solicitation of sex by guest-priests who were allowed to go into the area on temporary (weekend) parish assignments;

b. Alcohol and drug abuse by certain Paraclete members who were house superiors; and

c. The quality of the program.

Fr. John Feit was one of the superiors Fr. Murphy complained about. Feit submitted a response to Fr. Temple as did Fr. Gerald (Sept.30, 1966). Feit referred only to the quality of the program and made no mention of the other two points. Fr. Gerald claimed that any house superior who had abused alcohol was subsequently removed, and that at that time (1966) no superior had been intoxicated from alcohol or drugs in two and a half years. He defended the programs in place, but as to the accusation of guests soliciting sex he did not make any direct references. However, Fr. Feit's response made an oblique reference to serious misconduct, which probably referred to sexual misconduct since he had already confronted the alcohol/drug issue. His statement is an admission that in fact, such solicitation had happened: ·eIn isolated instances of serious misconduct the offending individual, when proven guilty, has been speedily dismissed from Via Coeli.”

The Murphy report was a significant element in the dispute over the direction of the community that lasted for two years.

Problems among the Paraclete Membership. There have been problems among the Paraclete membership. Several members had been guests there themselves. The most notorious is John Feit who had pleaded "no contest" to an abuse charge before he arrived at Via Coeli. Fr. Gerald admitted that Paracletes who were alcoholics had occasionally lapsed. The problem of alcoholic members who lapse has been recurrent over the years.

5. Fr. Gerald's Ministry Ends

The Island. Fr. Gerald had a very negative opinion of priests who sexually abused minors. In the 1950's he wrote to a number of bishops asking if they had an island in their dioceses where he could establish a totally isolated facility to permanently house such priests. Ironically, the bishop who responded was Archbishop Davis, then Archbishop of San Juan, Puerto Rico who had no idea he would soon succeed Archbishop Byrne. Archbishop Davis offered the island of Tortola but this was deemed unsuitable because it had several thousand inhabitants. In the early sixties the Paracletes established a facility on the island of Carriacou in the Diocese of Grenada. Fr. Gerald sent a down payment of $5000.00 as earnest money with a promise to pay the remaining $28,000.00 in future payments.

Archbishop Byrne died in 1963 and was succeeded by Archbishop Davis in early 1964. Fr. Gerald and Archbishop Davis did not share the close and supportive relationship that had existed with Archbishop Byrne. Fr. Gerald's total control of most aspects of the Paraclete ministry, the tangled finances, and the dispute over treatment modalities were the elements of a dispute that would last for two years.

Archbishop Davis ended the dispute with a series of decisions that would change the Paraclete community and the treatment they provided troubled priests.

The Archbishop sent a letter to Fr. Gerald on August 23, 1965. The letter contained eight "orders" that he was to carry out. He was to sell the island as soon as possible. He was to appoint Fr. William Tobin as superior of Via Coeli and Fr. McNamara as superior of the new foundation in Scotland. Finally, he ordered Fr. Gerald to accompany him to Rome for the fourth session of the Vatican Council. Fr. Gerald complied. This was the end of his authority. He never again resided at Via Coeli and although he retained the title of Servant General, he never regained the power he once had. Fr. Gerald died in Marlboro, MA on June 28, 1969 while giving a retreat. He was buried in the Paraclete cemetery in Jemez Springs on July 4, 1969.

6. Fr. Gerald and Clergy Child Molesters

Bishops and religious superiors were sending priests with sexual problems to the Paracletes at least from 1948 onward (cf. Letter of Fr. Gerald to a priest who had already been at the facility, 9-27-48). According to Fr. Gerald, half of the priests sent his way had alcohol problems and the other half had sexual problems. Concerning those with sexual problems, Fr. Gerald said that two out of five were cases of priests involved with women and three out of five were "aberrations involving homosexuality." (Letter of Fr. Gerald to Bishop Joseph Durick, 9-10-1964).